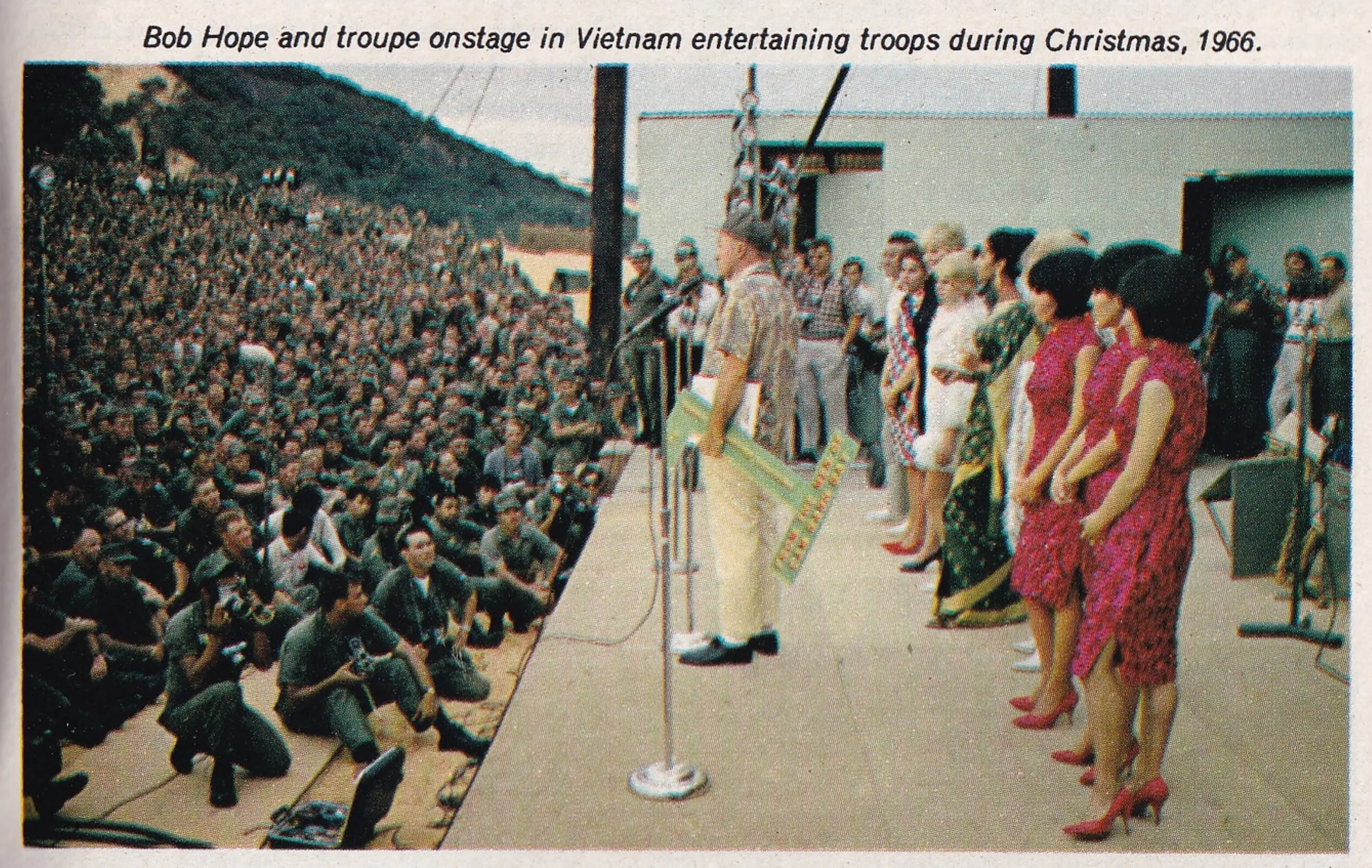

It was 7:30 in the morning of an unusually chilly December day in Los Angeles. A large crowd, including a U.S. Navy band, a Salvation Army contingent and Mayor Sam Yorty (dressed as Santa Claus), was at the airport to see Bob Hope off for his Christmas 1967 trip to Vietnam.

The band blared "Thanks for the Memory." A group of costumed kids sang "Jingle Bells." A rock group twanged. A Salvation Army chaplain led a prayer. Raquel Welch, in abrown minisuit, sat in her car for 45 minutes, isolated from the other members of the Vietnam-bound troupe. Then, when Hope arrived, she sprinted out to pose next to him for the photographers.

They all boarded a huge, windowless military plane-loaded with band equipment, costumes, personal belongings and beer (cases of it, stacked behind the pilot's compartment)-and then they were off on the road to Vietnam. (The tour will be recounted on Hope's NBC special this Thursday Jan. 18.)

It was the beginning of the latest in a long skein of visits to servicemen that have found Hope in many more parts of the world than he and Bing Crosby saw in the seven "Road" movies, which took them from Singapore to Rio. There have been a lot of memories crowded into a quarter-century which began at March Field, Cal., in May of 1941. "That was months before we got into the war," says Hope. "We must have had a premonition."

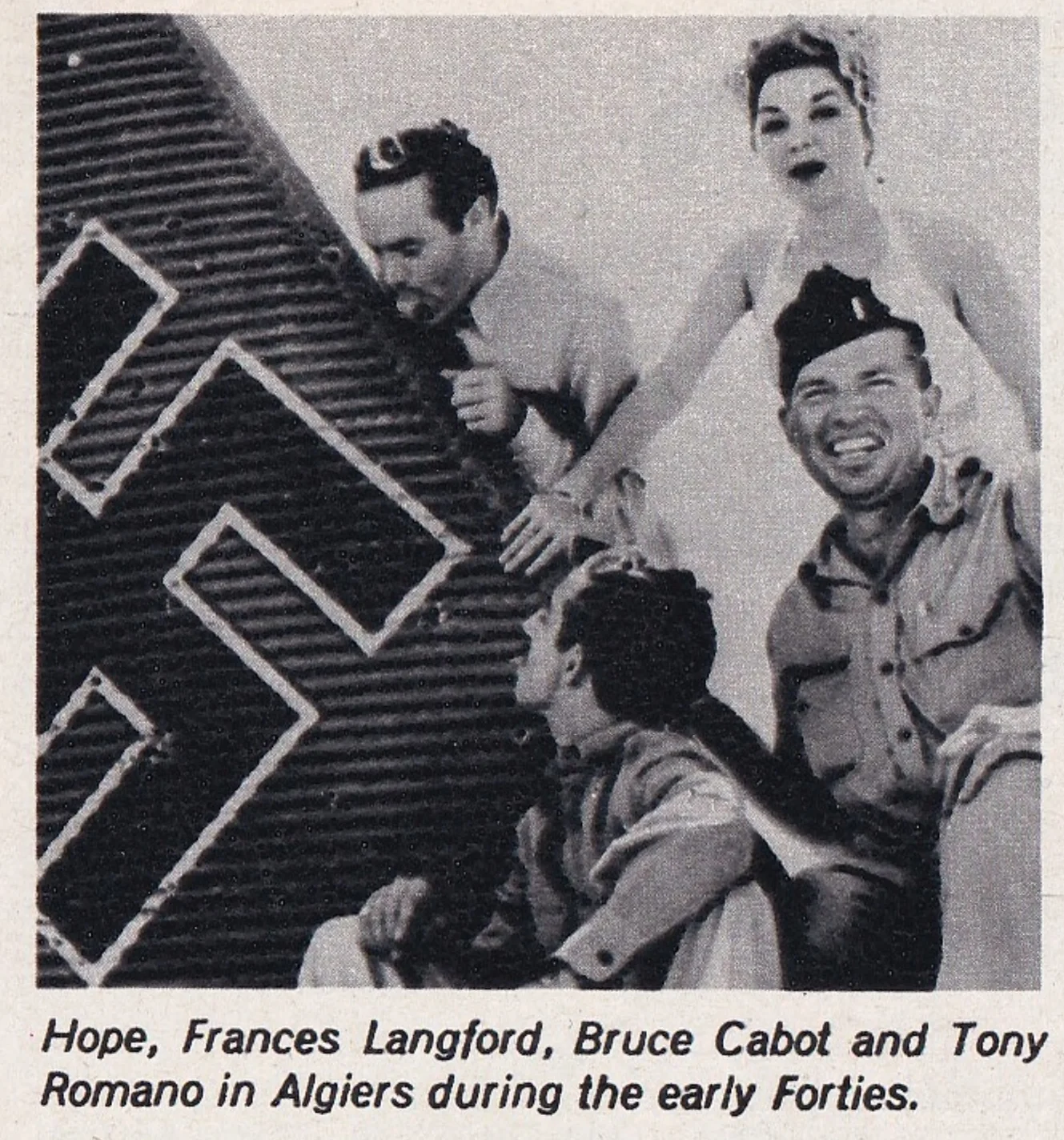

During World War II, the comedian did his radio show from a different military installation every week. "I loved it," he says, "and I still do. I've always been more or less of a gypsy. In vaudeville, I not only traveled all the time but did benefits every chance I got. As far as I'm concerned, the first day you're not doing something is a disaster day."

He has entertained an audience of 30,000 in Marseilles during World War II and an audience of eight at Northway, a refueling stop between Anchorage and Fairbanks, Alaska. "At first there were just these three or four guys-the night shift was on duty when we landed," Hope recalls. "One of them said, 'Hey, we're in the service, too. How about doing a show for us?' So I got up on a stump and started telling some jokes. While I was talking, the day shift guys woke and stuck their heads out of the tent flaps. At first they couldn't believe it. Then they started coming out, one at a time. Finally there were eight of them."

Hope has done shows while he had a temperature of 102 and after receiving the last rites from a priest. As he puts it, "When the band starts, you gotta go." On his first trip to Vietnam, there was a bullet hole in the plane, and he has put on shows within two miles of mortar fire. Some years before, as he left the stage at Pyongyang, Korea, he passed a dead child in the road ("He had just been shot"), and two weeks later saw pictures of the stage where he had performed burning after an air raid. Last year, captured Vietcong documents revealed that he and his troupe missed a planned bombing of the Brinks Hotel in Saigon by 10 minutes.

Sometimes it is difficult to go on and be funny, not because of any imminent danger to the entertainers but because of what they know about the men they are to entertain. Hope recalls, "In '44, we played before 15,000 Marines on an island in the South Pacific. We knew that they were invasion troops and that half of them would never come back. Later we found out that 60 percent of them were knocked off."

It is things like this which make him resent critics who say that he entertains GIS because they are such a responsive audience. "Just as if I'd go out there because it makes a good show!" he snorts.

On a trip to Tunis in 1943, Hope spotted a familiar face in the audience. He says, "Before the war, there was this guy that used to stand by the gate at NBC every week and ask if I had an extra ticket to the show. I'd always give him one, and he was always there. When I walked onstage in Tunis, there he was in the audience, in uniform. He just sort of waved at me casually-you'd have thought we were back in Hollywood."

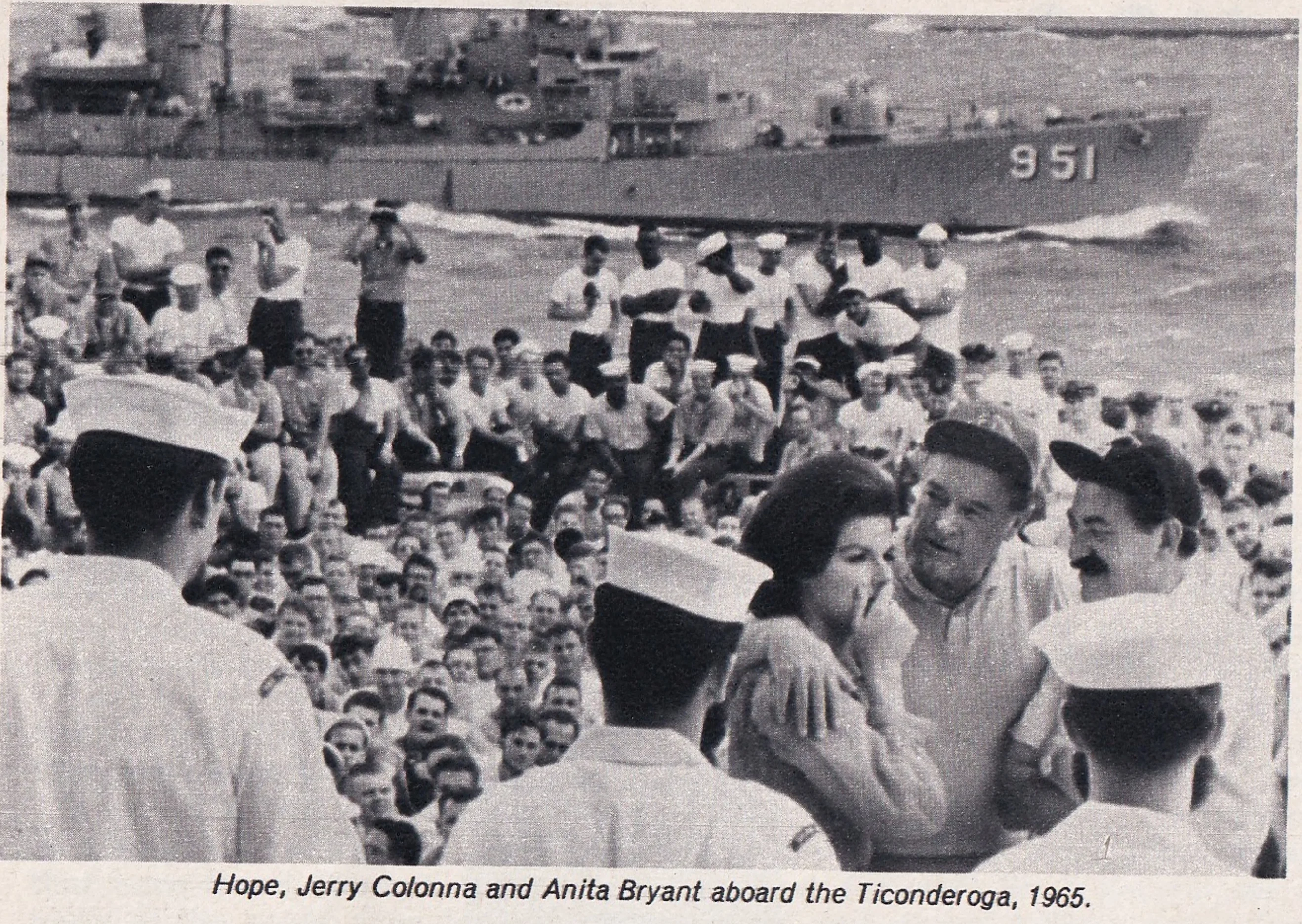

Name a military installation, and Bob Hope has probably been there. It is estimated that he has traveled 6,000,000 miles-innumerable trips during World War II and the Korean conflict; Berlin during the air lift of 1948; Alaska in 1949; the Pacific in 1950; Greenland, 1954; England and Iceland, 1955; Alaska again in 1956; the Orient, 1957; the Azores, North Africa, Iceland and Europe, 1959; the Caribbean, 1960; Newfoundland and Greenland, 1961; the Orient again in 1962; the Mediterranean, 1963; and South Vietnam and other Far Eastern bases in the years since.

He has received more than 700 awards and citations, including the Medal of Merit, presented by General Eisenhower; a tribute signed by 1,000,000 GIs, presented by President Truman; a gold medal authorized by Congress and presented by President Kennedy; and a USO plaque presented by President Johnson.

But a few blocks from Hope's Palm Springs home is a man who knows a side of the comedian which is not mentioned in the citations nor ap- parent in the flip Hope jokes. His name is Don Kimsey. During the Korean War, a badly wounded Marine, he was pushed forward in a wheel chair to sing for Hope. After his performance Hope told him to get in touch with him when he got back to the States-that he might be able to help him. Kimsey did exactly that, and Hope got him on television. Eventually Kimsey became a vocalist with Tommy Dorsey's orchestra. Now, as a soloist, he stars at one of the swank Palm Springs hotels.

Although Hope is proud of the roomful of awards and citations he has received, he undoubtedly gets more satisfaction from what he has done for ordinary GIs like Don Kimsey -whose story, by the way, he did not tell himself. Now, after more than a quarter of a century on the road, he says, "It's a lot of work-from the time you wake up in the morning until you go to bed at night, you never have a minute. But it's a very exciting, gratifying thing, and I wouldn't have it any other way." Neither would a few million GIs.

.jpg)

Social Plugin